October 13, 2015

By Ross Winstanley

There’s probably not been a more important investment of Recreational Fishing Licence (RFL) funds in marine fisheries research than the study by a Fisheries Victoria research team into the condition of the Port Phillip Bay sand flathead stock. The 2009 stock assessment had identified an alarming decline in flathead numbers and speculated on possible causes, including the 1997-2010 drought and the “explosion” in numbers of the exotic northern Pacific sea stars in the Bay. In response, anglers virtually commissioned a team led by Alastair Hirst and Paul Hamer whose report The decline of sand flathead stocks in Port Phillip Bay: magnitude, causes and future prospectssheds new light on factors affecting flathead numbers and the prospects of a recovery.

Importantly, this study teases apart those environmental factors that drive annual recruitment and over which we have no control from fishing impacts and possible fisheries management responses. Anglers account for more than 95% of the annual catch from the Bay so, if there’s a problem with a fisheries management solution, it’s up to us to recognise and meet it head on.

BACKGROUND

This study combined information including commercial and recreational fisheries, annual trawl survey and sand flathead recruitment monitoring data. Until 1960, the commercial fishery landed 150-300 tonnes of flathead annually from the Bay; most of the catch would have been sand flathead, with some Yank and rock flathead. Since then, with the growth in the supply of quality offshore trawl fish, the commercial flathead catch from the Bay has fallen to around two tonnes a year. Over this whole period, sand flathead have been the “bread and butter” catch by anglers, estimated at 322 tonnes in 2000/01.

Sand flathead can live for up to 23 years, with females growing to larger sizes than males. Males reach sexual maturity at 2-4 years, at lengths averaging 22 cm; females mature at 3-5 years and around 25 cm. Larvae occur in the water column between October and April, peaking in November, before settling on the bottom, mainly from December till February. Eggs are released and fertilised in the water column where larvae occur for periods estimated at 30-40 days. With most, if not all, recruitment originating in the Bay this larval stage is critical in determining successful recruitment to the stock.

During the early years of the 1997-2010 drought, crabs, other small crustaceans and marine worms were prominent in sand flathead diets but from 2000, pelagic fish – notably anchovies – and bottom fish became more important.

TRENDS IN THE BAY STOCK

Fisheries Victoria’s annual trawl surveys ran from 1990 till 2011, providing data that enabled trends in sand flathead numbers to be linked with annual spawning success and seasonal environmental factors. Trawl data showed that the recent decline in sand flathead numbers coincided with the first records and subsequent rapid population growth of northern Pacific seastars in the late 1990s. This observation prompted the questions about whether the seastars were implicated in the decline in sand flathead numbers.

In 1990 when the trawl surveys began, the sand flathead stock was estimated to be 3000 tonnes. The stock appeared to be in slow decline until 2000 after which estimates to 2010 showed a rapid decline of 87%. This was reflected in falling commercial and recreational fisheries catch rates. Detailed studies indicated that the 2008-2010 Channel Deepening Program played no part in this overall decline in sand flathead numbers. The final year of the trawl survey indicate that the stock increased from 400 to 464 tonnes in 2011. Commercial and recreational catch rates reflected the same upward trend. As with other biomass peaks from 1990 to 2000, this modest increase matched strong year classes entering the population at the larval stage.

Comparison of sand flathead growth rate estimates show that they have slowed since the 1970s, particularly during the first four years of life. Females now take four years and males up to 12 years to reach legal size in the Bay. With females growing faster and to larger sizes than males it’s not surprising that twice as many females exceed the legal size. The largest sand flathead taken in 21 years of trawl surveys was 41 cm long and the oldest were 23 years, although few survive beyond 16 years.Elsewhere in coastal waters and embayments in southern Australia, female sand flathead grow to 50 cm and males grow to 40 cm, both also living for up to 23 years.

The study found no link between the extended drought or the rise of northern Pacific seastar numbers and sand flathead growth rates.

Figure 1: Trend in sand flathead biomass in the Bay 1990–2011

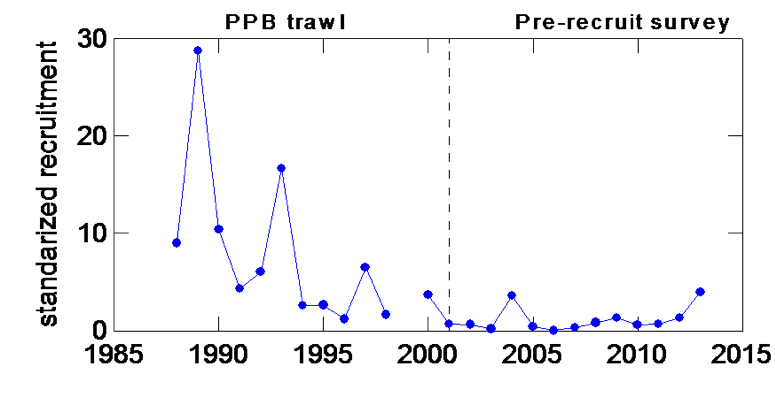

Figure 2: Combined measures of annual recruitment of sand flathead in the Bay from annual trawl and pre-recruit surveys over the period, 1988–2013.

WHAT’S BEHIND THE RECENT STOCK DECLINE?

At the same time as the 20-year 87% decline in sand flathead biomass, the study found there was a substantial drop in annual recruitment or spawning success in the Bay. The most recent large recruitment event was in 1993; since then the best there’s been are modest events in 1997, 2000, 2004 and 2013. The importance of strong year classes in maintaining the stock is illustrated by the fact that the strong 1989 year class was still detectable in catches 16 years later. The challenge now is how to “encourage” greater spawning success from a depleted stock with a fishery that targets the largest mature females. There is one bright spot – the 2013 recruitment pulse is the highest measured since 1997 when the flathead biomass was six times greater than at present. This emphasises the point that, even from a small base, stock recovery should be possible given favourable environmental conditions.

Clearly, the 1997-2010 drought was the most extraordinary environmental event that coincided with the years of biomass decline and poor recruitment. Its impacts on the Bay made it an obvious area to look for an explanation. As the timing of hatching and larval duration suggested that conditions in November and December are likely to be critical to survival, this period was studied in detail for possible environment-recruitment relationships in the Bay. The Yarra River accounts for 70% of all catchment flows into the Bay. Unsurprisingly, its flows decreased through the drought along with nutrient inputs from the Werribee sewage treatment plant.Nitrogen in particular is essential to stimulate phytoplankton productivity that provides food for zooplankton which in turn feed fish larvae.

The study looked for relationships between annual recruitment and daily November-December averages of four variables – stock size, temperature, wind speed and Yarra River flows.The one variable that accounted for a significant degree of recruitment variation was river flow during this critical spawning season. There is a clear positive relationship between Yarra River flows and sand flathead recruitment at flow rates up to 3000 ML per day.

PROSPECTS FOR STOCK RECOVERY

The researchers found no evidence of overfishing or indications that fishing pressure contributed to the rapid stock decline observed since 2000. They noted that, even as an almost recreational-only species, sand flathead are often taken as bycatch. When numbers become low, anglers are more inclined to switch to Yank flathead and other species rather than intensify effort directed at sand flathead. Nevertheless, they pointed to the need for a review of fisheries management arrangements, given the potential for fishing to impede recovery from the current low stock size.

Now is the time for anglers, along with Fisheries Victoria, to press ahead with such a review. It’s our fishery and it’s been our investment of RFL funds that put us in a position to make informed decisions and to act. The results of this study give us two strong points of encouragement towards a recovery. First, substantial spawning success and a real boost to recruitment is possible from a small stock size. Second, 2013 saw the most successful spawning event in 16 years; this should boost the adult stock over the next few years, adding to the early signs of recovery observed since 2010 and a platform for further improvement.

When and how far such further improvement might occur will depend on seasonal spawning conditions – largely beyond our control – and angling pressure on legal-sized breeding female sand flathead. Managing angling pressure is the immediate focus; we asked our best fisheries scientists for advice and they’ve given us a clear direction. They point out that changing the daily bag limit for sand flathead in the Bay is the only obvious management tool available. While the current bag limit is 20/day, 85-90% of angler trips surveyed from 2009 to 2013 caught five or fewer flathead. Modelling indicates that halving the bag limit could reduce the total catch by 4% while a bag limit of 5/day could reduce the annual catch by 16%. That’s the sort of measure we need if we’re serious about helping the sand flathead stock to rebuild. While the expected increases in stock size each year are in the order of 2-4%, the compounding effect over the next 10 years could be significant.

Underscoring the need for an urgent and decisive fisheries management response, the researchers point out that the longer term prospects for favourable larval recruitment conditions are not encouraging. Since the damaging long-term drought broke in 2010, the immediate outlook for favourable larval recruitment conditions has improved with the return to the “normal” range of Yarra River springtime flows. How long these conditions will occur is uncertain as global warming is expected to produce drier conditions on average. In south-eastern Australia, reduced rainfall and increased temperatures and evaporation rates are expected to reduce run-off by 20-36% by 2060.

Of course, anglers should be encouraged to take every possible measure to return sand flathead to the water unharmed and to minimise gut-hooking. Tasmanian studies have shown that, properly handled, 100% of lip-hooked sand flathead can survive and that more than 99% caught on circle hooks can survive after release.

OTHER BAY FLATHEAD SPECIES

The research and recommendations described here refer to sand flathead; there are two other flathead species taken in the Bay – Yank or blue-spotted flathead and rock flathead. At the same time sand flathead numbers were declining, the Yank flathead stock remained steady and was estimated to be 180 tonnes in the final year of the annual trawl survey, 2011. Yank flathead caught by anglers are consistently larger – by an average 7 cm – than sand flathead. While their stock size is not known, rock flathead are also commonly taken at larger sizes, particularly by anglers using soft plastics. As most rock flathead are taken by commercial fishermen using nets, over the next few years as netting is phased out, rock flathead numbers can be expected to increase.

A FINAL MESSAGE

Fisheries Victoria’s research team has delivered a thorough report that squarely addresses anglers’ concerns about Port Phillip Bay sand flathead and gives the clearest possible pointers on management actions and continued monitoring. It looks like an excellent investment of RFL funds and warrants an equally thorough evaluation by anglers and fisheries managers.

The executive summary of the report The decline of sand flathead stocks in Port Phillip Bay: magnitude, causes and future can be seen at http://agriculture.vic.gov.au/fisheries/science-in-fisheries or email: [email protected] for acopy of the full report.